Tom is a computational ecologist at the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (UKCEH) and works at the Biological Records Centre. Tom is interested in the intersection between citizen science, technology and academic research, and is now working on bringing them together. Most recently, Tom has been interested in computer vision and how it can support citizen science and the long-term monitoring of biodiversity in the UK.

Photo and credit: Tom August.

Can you tell me a bit about the work you do at the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (UKCEH) and the projects you are involved in?

I work at UKCEH at the Biological Records Centre, which is one of the national foci for citizen science in the UK. We are primarily academics but there are also web and app developers in the team – and many academics at UKCEH are also citizen scientists. We primarily collaborate with citizen science or citizen-led organisations and help the recording community to analyse their data, publish atlases and other online resources, providing information essential for research, policy and conservation. We are involved in over 80 recording schemes and societies such as the UK butterfly monitoring scheme, the pollinator monitoring scheme, and ladybird survey, among many others. We validate, verify and analyse data and work on species distribution modeling and trends analyses using occupancy models. These trends typically feed through to national indicators and official statistics.

Besides the work that you do at UKCEH, the reason that I am interviewing you is that you use the Pl@ntNet-API, one of several technological services that the Cos4Cloud project is developing. When did you start using the Pl@ntNet-API?

I have always had an eye out for technologies that could be used in our work. I met Pierre Bonnet, Cos4Cloud partner and Pl@ntNet-API co-developer together with Alexis Joly, a few years ago and I was really impressed by his presentation of Pl@ntNet. From that, I was interested in doing a short-term scientific mission within the framework of a COST action: I went to visit Pierre and Alexis in the South of France to learn all about Pl@ntNet and about how we might be able to use the tools that they are developing in the work of UKCEH. Then I wrote an R package to allow people to interface with Pl@ntNet and came back quite excited about computer vision, and how we could use Pl@ntNet to support our science driven by citizen science.

The following year I ran a hackathon in the UK and we worked on an idea to feed images from Flickr into the Pl@ntNet-API to tell us what plants were in the pictures. We ended up publishing a paper on this called “AI Naturalists Might Hold the Key to Unlocking Biodiversity Data in Social Media Imagery”, which showed the pros and cons of this method: We pulled the images off Flickr for London with ‘flower’ either in the title, the tags or the description, and then sent that through the Pl@ntNet-API to help us identify the plants. That could only be done because the API existed.

All this sounds innovative! Beyond this, have you used the Pl@ntNet-API in any of your projects?

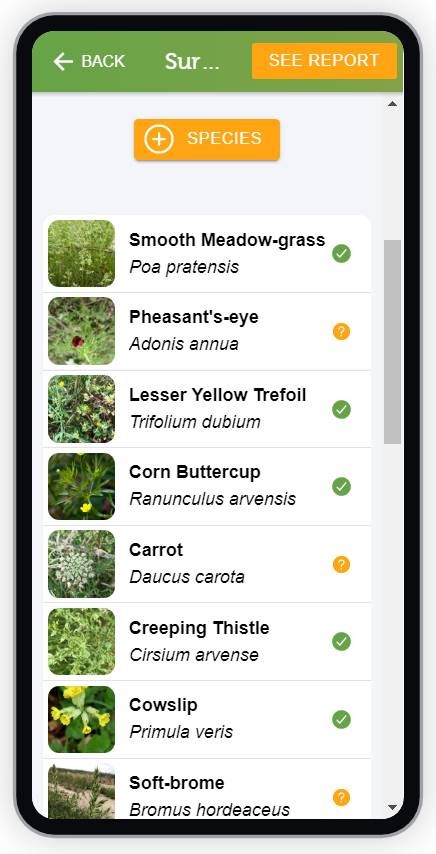

Definitely. At UKCEH, we also work on monitoring the agricultural environment. This work usually involves experiments asking the farmer to farm in a particular way and then expert surveyors monitoring the impact of different farming strategies by doing botanical surveys and other measurements. I was looking for projects that could use the Pl@ntNet-API, which we saw as a way to give farmers more agency and the ability to undertake some of these botanical surveys with the help of an AI for plant identification.We built an app called “E-surveyor”, a tool that allows farmers to monitor the habitats on their farms using the Pl@ntNet-API. We are interested in how much information we can provide back to the farmers. UKCEH holds datasets on plant-insect interactions and data on which plants host natural enemies of crop pests. Therefore, once the farmer does this survey supported by the AI, the app provides them information about the pollinators that their habitat is supporting as well as the insects which can be eating the pests on their crops.

This will help to raise awareness around the area of natural enemies and reduce pesticide applications. For example, if a farmer has many plants that are supporting ladybirds and they are going to eat aphids then they do not need to spray so much for aphids and could time their spraying in relation to how many ladybirds they have.

Photo: E-Surveyor interface. Credit: Tom August.

I consider E-Surveyor to be a citizen science app because we consider these farmers to be citizen scientists. Contrary to many citizen science projects focused on data collection that end with submitting data to a platform, we add that additional step where we provide a service back almost instantly. This project is more about providing information to the farmers rather than collecting data for ourselves.

E-Surveyor launched in June 2022 and the app is constantly being developed. You can try it out here: https://www.ceh.ac.uk/e-surveyor and give any feedback to esurveyor@ceh.ac.uk

So you knew about the Pl@ntNet-API first and then you developed the app E-Surveyor. Still, what problem were you having that Pl@ntNet-API helped you overcome?

The taxonomic barrier has always been there: an ecologist needs to be trained to be able to identify animals and plants and there is need for tools to help with identification. There have been continual evolutions and revolutions around breaking down that taxonomic barrier over time and helping with identification (Linnaeus’ nomenclature, dichotomy keys, field guides…). AI-assisted image classification to me is just another step along that journey. I often give talks about computer vision and AI and talk about the interaction between the recorder and the AI tool.

I think that Pl@ntNet navigates that interaction really well, both the Pl@ntNet app and the API. There are for me the two key elements of a good AI in these spaces: that they are honest and tell you the various things that could be and their scores; and that they give you the chance to falsify.

Pl@ntNet is very honest about what it sees and indicates confidence against each possible species (for context: after a user uploads a plant photo to the app, the service returns a list of species and the likelihood of the image being species ‘x’ or ‘y’).

It even goes further and provides a list of images of the identified species right next to other suggestions that the user can use to refine their decision, making it as falsifiable as possible. Not all AIs/apps do that. That is one of the great things of Pl@ntNet and we feed that into our app by using many of the API functionalities to make it as open and transparent to the users as possible.

Beyond the way that you are using the Pl@ntNet-API right now, what other uses do you envision it having for the work you do?

Verification is a big part of our work where expert verifiers review observations recorded by citizen scientists. We have talked about including AI image classifiers in this process. Observations could be classified by the AI image classifier when they first come in and the expert would see the result of the classifier when reviewing it. If the classifier were very confident about certain species, the identification could be automatically processed. This could be the case for the peacock butterfly in the UK, for example, a commonly observed, visually distinctive butterfly. This would save the experts time to focus on more difficult identifications. The Pl@ntNet-API could be used this way for a number of very distinctive plant species.

We have thought about this but we have not done anything yet in that area – because you need to know that the classifier performs well and get the verification community on board as well. There is a social element to this and how we develop trust in these sorts of technologies that are, by their nature, quite black-boxed: it is hard to tell how they work and why they have come to a particular classification for a particular species. To build in that trust is probably going to be a long process, but I imagine that we will eventually start to see these tools built into our verification platforms.

How do you imagine this evolving? Do you think this is just a matter of time and that the next generation will be more open to using these tools?

I think this is a combination of two things: the younger generation tends to be more accepting of change and new technologies; and the older generation being more comfortable in the way they have been doing things in the past. That is maybe part of it, but it is an easy way out for us to say this is not our problem. The other way to look at it is that we need to provide evidence to convince people that it works and show where it works. That is primarily what I am interested in: translating these technologies into applications that are actually going to impact the science that we do, and demonstrating how these technologies can work when being applied.

Visit the website of the Biological Records Centre to learn more about their work.

To learn more about Cos4Cloud’s services for citizen science, visit the project’s services description.