Maria Daskolia is a tenured associate professor in Environmental Education at NKUA and director of the Environmental Education Lab at the same institution. She holds a bachelor in Philosophy, Pedagogy and Psychology from NKUA, a postgraduate degree (MSc) in Environmental Psychology at the University of Surrey, and a PhD degree in Environmental Education at the NKUA. She has participated in and led several research projects, both national and European, and has published extensively on environmental education topics.

This multidisciplinary background has driven her to explore new, emerging and cross-cutting fields, combining apparently opposed scientific domains in dialectical and interdisciplinary ways, such as ‘psychology’, ‘education’ and ‘environment’ studies.

When asking her about her professional passion, she answers that she has always been more inclined in scientific research, theory and action that engage her students and herself in more holistic ways of understanding, participating and co-creating our complex socio-environmental reality. We can observe these threaded themes running through her academic journey.

Maria, your career is impressive. When did you start combining citizen science and education?

I believe I crossed paths with citizen science in a coincidental yet meaningful way! It started like this. In my university courses, I always emphasise the importance of participating as citizens proactively to transform our surroundings and co-construct our environmental reality.

In fact, the way I view and teach environmental education is as ‘citizenship education.’ That is, as a process that helps foster a range of lifelong citizenship mindsets and competencies, such as being vigilant, wondering and asking questions, investigating for the answers, being open to different ‘truths’ and participating in collective efforts for more sustainable futures.

Moreover, I always used to ask myself: how can I, as a person and a teacher, combine different genres of knowledge related to the ‘sustainability’ competencies, such as scientific information from nature and social sciences with personal insights and traditional experience, among other knowledge sources? That is why I started designing some transdisciplinary learning experiences and projects for my students attending my environmental education courses, such as going out in the real world, observing and recording various phenomena and situations with a range of means, and then sharing their data and interpretations of them with their fellow students or the community. This is how I started doing citizen science with my students without knowing it!

Is there any specific project that drove you to connect with the European citizen science community?

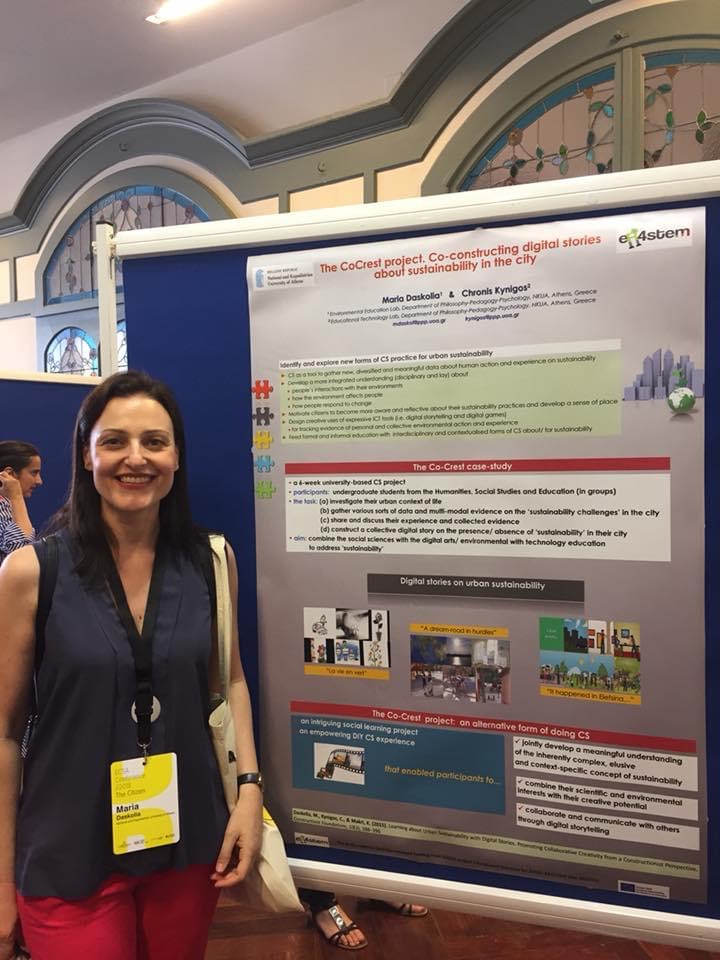

Yes, in particular, one of these learning projects was a kind of ‘mission’ to ‘go out in their city and capture images of sustainability’, firstly by taking photos, sharing them and discussing what they represent and how they interpret them and then co-creating digital stories on urban sustainability (to give examples of ‘good’ or ‘poor’ sustainability). This project allowed me to meet with the citizen science community at the 1st European Citizen Science Conference held in Berlin in 2016. There, I presented this story about engaging students with their local environments and communities by recording visual data of ‘sustainability’.

This conference was a huge learning experience for me because it made me realise the great potential of citizen science. I immediately felt I wanted to become part of this community; it made me feel comfortable, challenged and creative at the same time and keen to further explore the common grounds between environmental education and citizen science.

Following this, I sought more opportunities to participate in workshops and COST actions to exchange ideas and collaborate with some of the most prominent citizen science actors in Europe. The first successful chance for a creative partnership at a European level came up with Cos4Cloud and I am very proud of it. Due to this project, I became more actively involved with citizen science and had the chance to meet and work together with some really great partners.

Why do you think citizen science should be introduced as an innovative teaching tool in school curricula?

Through my personal involvement and teaching practice with environmental education, it has been evident to me that both ‘science’ and ‘citizenship’ are two cornerstones on which education has to lean on to build young people’s sustainability competencies. In addition, citizen science promotes scientific research and citizens’ participation in their local communities, highlighting the citizens’ active role in understanding the environment, contributing to knowledge production and co-shaping a better world. Moreover, modern citizen science uses new technologies and digital applications to advance its goals and open up to a broader audience.

For all these reasons, I think citizen science can be an appropriate, congruent and powerful tool for education and learning. It is high time to explore more and innovative ways of integrating it into school curricula as effectively and creatively as possible.

Can you tell me any “success cases”?

I can tell you about the positive impact I’ve experienced from the school case studies we organised and evaluated in Cos4Cloud. Then, I realised how positively school communities respond to citizen science’s innovations and its learning value.

In fact, one of the first “success stories” the NKUA has brought in Cos4Cloud is the online teacher training course we designed, organised and implemented to introduce citizen science into formal school education. A vital component of this course’s success was assigning teachers the role of ‘educational designers’ of integrating citizen science into school environmental education. This was a deliberate act of empowerment. The course thus led to the creation of six educational scenarios and a consecutive series of school case studies. But, perhaps the greatest “success story” comes from the teachers’ recognition that the whole experience was both creative and with a great learning potential for their students.

In Cos4Cloud, you lead the integration of citizen science into Greek schools. How did you come up with this idea?

This is how it is. Cos4Cloud is a project that mainly promotes technological innovation and the development of new services for citizen observatories.

In Cos4Cloud, the NKUA’s contribution has to do with a ‘softer’ kind of innovation but still a critical one: how to bring these technologies and services to school education communities. It is also to make citizen science known to the school population and find appropriate and creative ways to integrate it into school curricula.

Environmental education has a long tradition in Greece, starting from the 1990s and reaching our days. And there are many competent school teachers with much enthusiasm, wit and experience to support the design and implementation of environmental education projects. This is why the NKUA focused on Greek schools as an exceptional case study and we used environmental education for sustainability as a springboard to bring citizen science into schools.

During the six-month course you organised, you mentioned you created educational scenarios with the teachers. Which are the citizen science platforms you used to do it?

In the course, we demonstrated all Cos4Cloud platforms to allow our trainees to get to know all the main citizen observatories of the project. However, we had to decide which platforms and tools were most appropriate and ready to be used for Greek school students. For this reason, we chose Pl@ntnet to record plant species and identify them, and OdourCollect to monitor environmental quality through odours. However, some teachers opted to use more platforms and apps, such as Natusfera, combined with the other two.

From your perspective, what are the challenges in introducing citizen science into the school curricula?

I would say that the integration of any innovation in schools is quite a complex process. his is why a lot of research and many policy efforts have focused on identifying and analysing the success stories and trying different pathways to support the integration of innovations into schools. From my perspective, I think one key factor is ‘the teachers’. The challenge is helping and empowering them to be bold, creative and willing to experiment with something new. To do this, they need easy-to-use tools with added pedagogical value, respectful guidance and a supportive environment to express and structure their ideas on how to integrate innovations into their school practice.

As you said, teachers are essential to creating these new educational scenarios. How can we encourage and support them to be more innovative?

The key is to build these encounters and experiences with innovation with them and from the beginning, not to impose them. It is also essential to recognise them as ‘the experts in school practice’ and the ones who have the knowledge and experience to create meaningful learning experiences and clear learning outcomes for their students. This is why appropriate teacher training is so necessary and that all external support needs always to be based on trust, collaboration and mutual feedback.

What work are you planning to carry out before Cos4Cloud ends?

Our main emphasis will be on supporting the implementation and deepening the evaluation of new environmental education projects and activities in schools integrating citizen science tools and technologies.

We want to develop meaningful insights into the processes and mechanisms for integrating citizen science in school education and also define how Cos4Cloud’s technologies can foster learning.

Establishing a national educational network is also among our priorities and possibly its further growth to a European level. Finally, we plan to disseminate the results of all our initiatives and research as much and wide as possible.

Cos4Cloud will integrate the developed services in the new European Open Science Cloud (EOSC); why do you think this is important?

I think this will be a major achievement to the benefit not only of citizen science but also formal science and research, democracy and local sustainability. The EOSC is meant to provide multiple services as a Hub for scientists and policy-makers as well as citizens and practitioners to share and make use of scientific observations and data. It can also serve as a hub for education and learning. Furthermore, if connected to European schools, it can definitely open up new opportunities for a new paradigm of science and environmental education for the future.